Community connection and disaster resilience: An argument for makeshift architecture

My name is Genevieve Quinn. I am an architect, researcher, and resident of West End. My passion and interest in architecture lies within its potential to drive inclusion, equity, and social justice. When I was asked to contribute to this blog, I was excited to discuss this topic through the lens of a flood-affected suburb.

Firstly, I would like to acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land, the Turrbal and Jagera people. Throughout this article I will be discussing the impacts of floods on the area of Kurilpa. I want to stress the importance of truth telling and reconciliation when discussing both climate resilience and social justice.

The climate crisis is a phenomenon linked hand in hand with colonial ideologies. I would like to extend my gratitude to First Nations people who took care of the land and seas immemorial, and continue to fight for it.

The flood of 2022 was the first flood I faced while living in West End.

In the aftermath, I was struck by the support of the community as well as the sheer quantity of construction material that was disposed of due to the flood. Walking around and seeing piles of sodden timber outside of stripped Queenslander homes, perched on their stumps, catalysed my Paul Pholeros Foundation Scholarship titled “Makeshift Architecture for Flood Resilience”.

Image: Then Member for South Brisbane, Amy McMahon, standing in front of flood-damaged belongings waiting to be disposed of in February 2022.

Is ‘building back better’ affordable?

I was interested in how communities could ‘build back better’ when they couldn’t afford to ‘build back better’. A large part of the discourse around flood-resilient architecture and planning is the affordability factor. As Sebastian Vanderzeil discusses in his recent Local Insights post, flooding and financial stress are intrinsically linked.

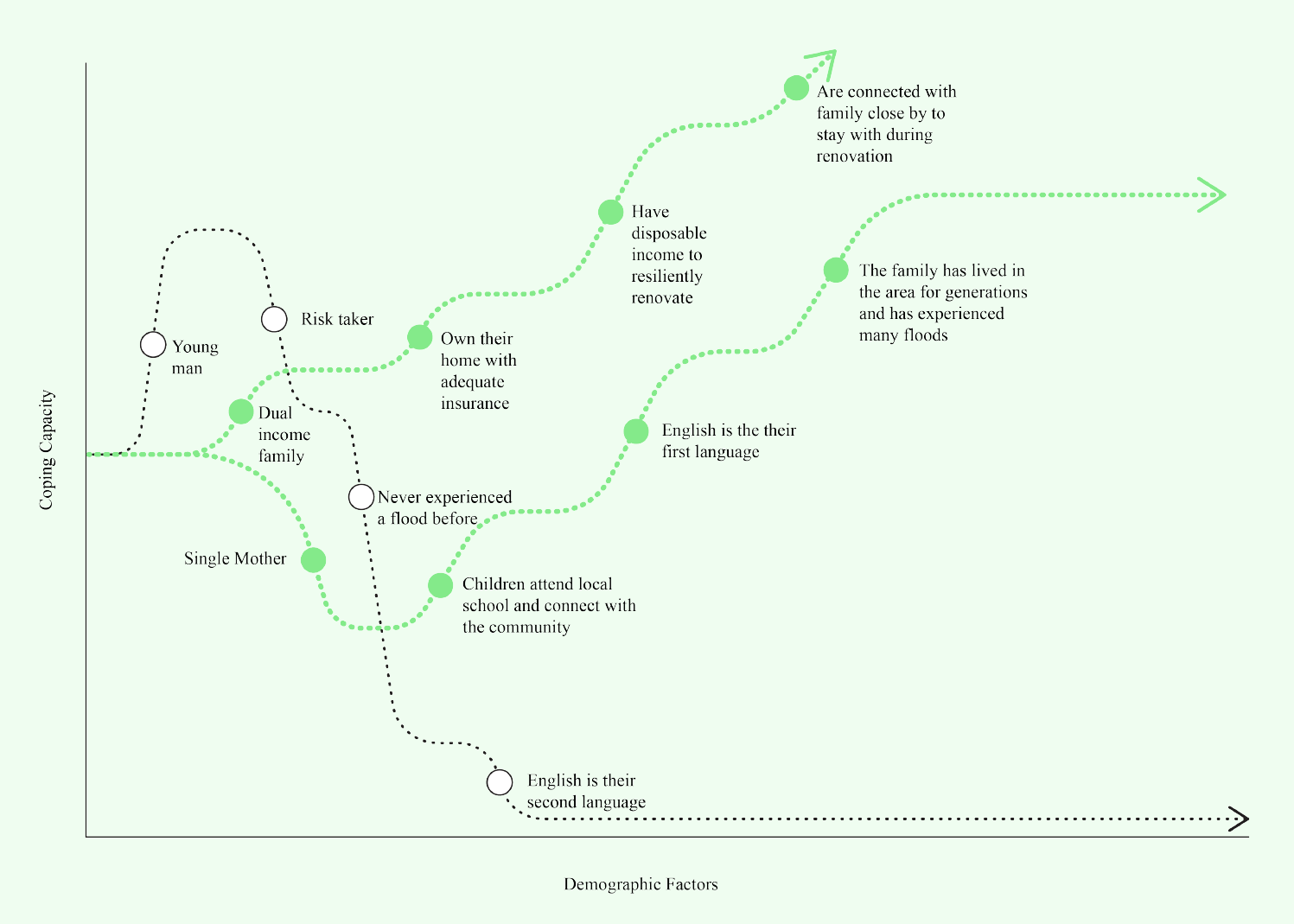

So, my research aimed to understand the impact of floods on various demographics, diving in the nuances of demographic beyond income, and propose an architectural idea to assist those who do not fall into the demographic to access an architecturally designed home.

Rich in connections = rich in resilience

Along the path of this research, I came across a study on the impact of various demographic factors on disaster vulnerability. This study focussed on the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and found that a person’s overall vulnerability to a disaster could be calculated based on a summary of many demographic factors, not simply income.

Image: This diagram illustrates how different demographic factors can impact an individuals ‘coping capacity’ during a disaster. The three fictitious people graphed represent common demographic or lifestyle factors in the Kurilpa area.

These factors included languages spoken, connection to neighbours, household members and if the person had a child attending a local school. The study found that those who had deep and strong connections with a community gained some resilience in a disaster situation. These connections could be formed in various ways.

In the study it was found that tightly knit diasporic communities proved to have an increased ability to recover from the event, despite seemingly disadvantageous demographic factors such as language barriers and socio-economic struggles. This finding does not negate that floods and natural disasters disproportionately affect those of lower-socio economic standing. However, it does provoke an interesting question for all residents of our community:

Can we bolster the overall resilience of our community by strengthening our connections?

This question does not serve to supplement the systemic and institutional changes that are required to ameliorate the many inequalities in current society. It does, however, consider what role the individual plays in the holistic wellbeing of a community facing a climate emergency.

Gentrification and the loss of connections

Looking at West End specifically, I do not need to prove that the community is connected. For generations West End has been known for its eclectic make up of diverse groups and community spirit. This diversity is what makes our suburb beautiful and sought after. However, it is also something that may fragment the community in the face of disaster, and something that is currently at risk.

Recent planning mechanisms that allow for high rise buildings to be constructed, primarily serving the luxury housing market, as well as the epidemic of once charming Queenslander homes being painted various tones of white, all point to rapid gentrification. While Jane Jacobs, in her architecturally canonical ‘The Death and Life of Great American Cities’ stresses the importance of casual social interactions in successful urban design, often, the symptoms of gentrification strip suburbs of the infrastructure that hosts these interactions.

In efforts to ‘clean up’, ‘modernise’, and ‘increase safety’, I worry that we are at risk of losing our social connection.

What is makeshift architecture?

I propose that ‘makeshift’ architecture is one element that we can use to increase our social connection and community resilience, and something I would encourage everyone to consider when occupying the streets.

Wandering around Kurilpa, it is not hard to find existing pieces of makeshift architecture.

The plant stall on the corner of Vulture Street and Hardgrave Road is a perfect example. A few tables shaded by a leafy tree serves many purposes. It provides income to a local resident, a place to pause and rest on the sunny walk home from the markets on Saturdays, and a place to have a chat with neighbours.

While it may seem like a small part of our built environment, I would argue that it is a very important piece of social infrastructure.

Similarly, the xylophone (previously piano) at Bunyapa Park, a seemingly trivial addition to the park, constantly draws people of all walks of life to it.

Image: The local plant stall, a fixture in West End.

Image: Xylophone in Bunyapa Park.

Let’s keep building makeshift architecture

So, my call to action for everyone reading this is to, firstly, make use of the makeshift architecture you encounter. Put a book in that mini library on your street, use the pizza oven in Paradise Park, buy a plant from the stall on Vulture Street. Not only will it bring you a little bit of joy, but it will also contribute to our suburb supporting itself through the many floods that we are certain to face in the future.

Secondly, this call out is to all of those who have the means to generate makeshift architecture. There are many beautiful examples of architecture that contributes to social interactions and community connection.

A exquisitely refined approach can be found in John Ellway’s Hopscotch House. The architect, Ellway, positions an outdoor seating area on the boundary of the site.

When its occupants sit there, they become part of the streetscape, connected with passersbys and their neighbours.

Images: The front view of John Ellway’s Hopscotch House showing its fence/seating area hybrid. And a floor plan of John Ellway’s Hopscotch House. On the top left of the plan, a seating area on the street can be seen.

In a more modest approach, I have always loved walking past my neighbours’ houses and seeing their hand made boundary wall-turned seat.

A simple timber platform added on top of a blockwork retaining wall allows a parent to comfortably supervise two households’ of children play. In the evening, I have spotted the adults having a drink and socialising, perched on their boundary wall seat; a sight which is sadly not common in our streets anymore.

There are many ways to increase our social connection in Kurilpa.

Makeshift architecture is just one way. However, I believe it is a potent tool we can use for flood resilience and one we should be protecting.

So, as an architect, and a member of our community, I would like to officially endorse makeshift architecture and challenge anyone who has the ability to, to lower your six-foot fence and add a seat, plant a fruit tree in your verge, and paint your house a beautiful non-beige colour.

It might just start a conversation that will turn into a helping hand in the face of disaster.

Relevant links:

https://architectureau.com/articles/design-research-that-tackles-floor-reconstruction/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212420915300935

https://www.jellway.com/hopscotch-house

Genevieve Quinn is an architect, researcher, and resident of West End. Her passion and interest in architecture lies within its potential to drive inclusion, equity, and social justice.