Caring for Maiwar

1 September 2024

For residents of Brisbane, and particularly Kurilpa, the Brisbane river is an ever-present source of both enjoyment and menacing threat. What can one day provide a pleasant place to sit by and enjoy a picnic with friends and family can the next destroy everything in a matter of hours. How then can we live alongside and care for the river? It must start with understanding.

Local elder Uncle Willie Prince says before colonisation the Brisbane River on both sides was bordered by lush green rainforest with abundant wildlife. The river was a vibrant and complex ecosystem, deeply intertwined with the lives of the Turrbal and Jagera Peoples. The river, known as "Maiwar" to some groups, was central to their culture, spirituality, and sustenance, providing an abundance of resources and acting as a natural highway for travel and trade.

Image: Knowledge card from the Kurilpa Flood Library. Read more here.

Brisbane historian Ray Kerkhove’s report on Indigenous Heritage around the Brisbane River in the inner city includes eyewitness accounts of what the Kurilpa peninsula looked like in the early days of colonisation.

…giant vines stretched octopus-like arms around yellowwood, pine, and fig. The native grape-vine grew in abundance, bearing dusters of small purple berries, which in season attracted wild pigeons from the hills beyond Coorparoo. Owing to the dense foliage overhead the sun's rays never played upon the little stream which purled over a pebbly bottom in the centre of the scrub.

This jungle was a tangled mass of trees, vines, flowering creepers, staghorns, elkhorns, towering scrub palms, giant ferns, and hundreds of other varieties of the fern family, beautiful and rare orchids, and the wild passion flower. While along the river bank were the waterlily in thousands, and the convolvulus of gorgeous hue…dense vine-clad jungle, festooned with the blue and the purple convolvulus, while on the tidal brink grew the beautiful salt-water lily - its flower white as alabaster, its glorious perfume filling the air with fragrance. Kingfishers - some scarlet breasted, others white, all with backs of azure blue, - darted hither and thither, while anon the solitude was disturbed by the raucous laughter of the kookaburra.

Image: A view of Hill End from Toowong in 1885 before the construction of houses along the river bank. (State Library of Queensland

Swamps and strings of waterholes fed into the river, the Gabba being one former waterhole. acting as natural buffers against flooding and serving as critical habitats for waterbirds, amphibians, and reptiles. These areas were seasonally inundated, creating rich feeding and breeding grounds for wildlife.

But the arrival of European settlers in the 19th century dramatically altered the ecology of the river. Deforestation, agriculture, and urban development led to habitat destruction, pollution, and changes in the river’s flow. Wetlands were drained, and the natural vegetation was cleared, leading to a decline in biodiversity.

Over time, the river became heavily modified, with the construction of dams, weirs, and other infrastructure further impacting its ecological health. The river was also dredged regularly to allow boats to come further up. And while dredging can reduce flooding it can also make it worse.

According to CIWEM (Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management),

“targeted dredging can only ever have the potential to reduce flood risk when there is a sufficient understanding of how flood water peaks move through the system. Without an understanding of this very complex picture, there is significant potential to worsen flooding”.

It is terribly sad to think of how much has been lost, but realistically we can never return the river to its pre-invasion state. How then can we live alongside the river, care for it and, in doing so, perhaps better manage future flooding?

In many places around the world, people are approaching this exact issue as flooding increases, especially in areas where the river systems have been disturbed by modern infrastructure, deforestation, and pollution.

‘Living shorelines’ in Maryland, USA

In Maryland, USA, the state government has been providing incentives to residents with properties on the river since 1968. “The Shore Erosion Control Revolving Loan Fund [provides] financial and technical assistance to property owners who take measures to protect eroding shorelines. The fund offers 5, 15, or 20-year loans”.

However, this money was often used to construct hard barriers—retaining walls and bulkheads—which only stop erosion temporarily and can damage the ecosystem by damaging shallow water vegetation where small fish and crustaceans live. They also deflect wave energy from surging water causing damage to other properties.

In 2007, the Maryland Commission on Climate Change recommended the use of “Living Shorelines” rather than the hard structures. This involves the use of natural materials such as plants, sand and rock, but also native plants. These softer structures absorb about half the wave energy caused by surging river water, thereby reducing damage.

Stabilising riverbanks and preventing erosion prevents the river from widening and becoming shallower, factors which contribute to flooding. Planting trees, shrubs, and grasses along riverbanks also increases water absorption. These measures also reduce the buildup of sediment in river channels, which can otherwise cause the river to become shallower, thereby increasing the likelihood of flooding.

Image: Before and after shots of a waterfront community in Arnold, Maryland who replaced failing bulkhead with natural living shoreline to improve water quality and create wildlife habitat. Chesapeake Bay Trust.

Restoring a natural watercourse in Seoul, South Korea

If restoring a river seems an impossible task in an established city, then consider the restoration of the Cheonggyecheon River in Seoul, South Korea, a city that has been heavily inhabited for over 2000 years.

While it has not been restored to its original state, nevertheless the Cheonggye Creek, as it is called, is now a green oasis where before a raised motorway ran since 1968, obscuring the remnants of the old city’s coastline, in a similar way to the motorway that protrudes out from the Brisbane River bank. Restoration involved creating a new traffic model to redirect the 168,000 cars that used the motorway daily.

Apart from creating a beautiful green space in a busy city “environmentalists have mentioned a plethora of additional advantages of this activity”. These include:

flood protection that “can sustain a flow rate of 118mm per hour”;

an increase in biodiversity of both plants and animals;

a decrease in temperature of 3.3-5.9 degrees celsius along the stream;

a 35% reduction in air pollution

“Before the restoration, residents of the area were more than twice as likely to suffer from respiratory disease as those in other parts of the city”.

Image: Cheonggyecheon River, South Korea. Source.

So what does all this mean for Maiwar?

We can’t fully return the river to its pre-invasion state, and flood plain development, however unwise, appears unlikely to slow any time soon without stronger political pressure. The natural watercourses that existed before development and provided some flood mitigation are gone.

In Margaret Cook’s book A River With a City Problem, she describes the blaming that went on after the 1974 floods saying “The Courier Mail editor cited evidence of creeks filled in and natural areas of flood mitigation altered to ‘provide playing fields, industrial and housing estates, and other purposes’”. The Somerset and Wivenhoe dams were touted by Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen as being the solution to flooding in Brisbane, effectively allowing developers carte-blanche to build on the flood plain, but according to Cook’s book:

“The Premier’s own department acknowledged the enduring risk in a briefing note for the [Wivenhoe] dam’s opening. Future floods were inevitable and the author ‘hoped further movement into the floodplain would not occur’ after the dam’s construction… Modern international floodplain management included flood plans and mapping, public education, acquisition of repeatedly flooded properties and federal insurance. But in Queensland these strategies were ignored”.

Image: Knowledge card from the Kurilpa Flood Library. Read more here.

Since 1974 Brisbane’s population has grown from 940,000 to over 2.5 million. Hence the explosion in housing development in inner city suburbs. But compared to other cities around the world, Brisbane is a young city; if a city as ancient as Seoul can do something about restoring a river, surely Brisbane has the capacity to care better for its river.

In the Netherlands a project called Room For The River has literally made more room for water to flow at thirty locations along the four rivers that make up the delta. But these are major engineering projects involving deepening beds, moving dykes, and creating branches to channel water around inhabited areas.

Image: Knowledge card from the Kurilpa Flood Library. Read more here.

Community-level approaches to river care

Still yet, local citizens are able to make a difference to the health of rivers and hence their behaviour. Here are some examples:

Friends of the Chicago River organise regular clean-up events where volunteers remove rubbish and debris from riverbanks and water. In doing so they claim to have improved biodiversity and have helped “mitigate flooding, air and water pollution, and the urban heat island effect”.

India’s Rally for the Rivers, initiated by yogi and guru Sadhguru, has restored the health of its rivers by rallying 162 million people from sixteen states to revegetate the land. In so doing, for example, local communities in Maharashtra have revived the once-dry Waghari river by desilting, building check dams (small, often temporary, dams that can slow water flow), and planting trees along riverbanks.

Perhaps more relevant to Brisbane is the work happening in Lismore to restore and manage the Richmond River. As people are well aware, Lismore suffered terribly in the same floods that inundated Kurilpa in 2022 and, as a result, realised the need to look to the health of their river. The project, under the guidance of Professor Amanda Reichelt-Brushett at Southern Cross University, is part of a global organisation called Waterkeeper Alliance, “community-based advocates united for clean, healthy, and abundant water for all people and the planet”.

While the Lismore community had long been aware of the state of the Richmond River, the 2022 floods truly exposed the vulnerabilities of the system. As a result, Richmond Riverkeeper was established in December 2023. With the poorest water quality among New South Wales' coastal rivers, the Richmond River, which runs through Bundjalung and Githabal land, has suffered from historical land use issues similar to that of the Brisbane River, such as the clearing of the Big Scrub Rainforest and draining of wetlands, leading to erosion, sedimentation, and blackwater events (when flooding washes organic material into waterways, where it is consumed by bacteria, leading to a rise in dissolved carbon in the water, thus turning the river ‘black’ and depleting oxygen).

Flooding highlighted the need for action, but short government cycles and fragmented local governance have hindered long-term river health improvements. Inspired by the success of the Yarra Riverkeeper, Richmond Riverkeeper was founded to give the community a voice and advocate for sustainable river management. The project aims to work with local land-holders and Indigenous land councils to better understand what is needed to restore the river.

According to Professor Reichelt-Brushett (speaking on the website video):

“The Richmond River catchment has been modified considerably in the last 150-odd years… the fact that we’ve cleared so much vegetation upstream, the consequence of that is we’ve had major infilling in the downstream areas. We can see we’ve had large banks being eroded and slumped into the river. We can see that the water clarity isn’t very good. We’re out of balance and it’s really important that we work towards bringing the system back into balance.”

The organisation is in its infancy, but has already launched a citizen science project to assess the health of the river “a major component" of which is “examining the type and number of macroinvertebrates (water bugs) collected. This can tell…a lot about how healthy or unhealthy a river is because different macroinvertebrates have varying sensitivity to pollution”.

Image: Professor Amanda Reichelt-Brushett on the future of the Richmond River Catchment. Source.

So what actions can we take to improve the health of a river and thereby influence flood mitigation?

River Clean-Up Campaigns: Removing trash, debris, and other obstructions from rivers and their banks helps maintain clear water channels. This ensures that water can flow freely during heavy rains, reducing the risk of blockages that can lead to localised flooding.

Community-Led Restoration Projects: Projects like desilting rivers and constructing check dams slow down water flow and increase water retention in the soil. These measures reduce the volume of water rushing downstream during heavy rains, which in turn decreases the likelihood of flash floods.

Advocacy and Legal Action: By holding polluters accountable and ensuring stricter environmental regulations, advocacy efforts can lead to better-managed river systems. This includes the prevention of illegal dumping and deforestation, which can exacerbate flooding by increasing runoff and reducing natural water absorption.

Educational Programs: Education about the importance of maintaining natural vegetation and proper land use helps communities adopt practices that reduce runoff and erosion. This leads to better soil stability and more efficient water absorption, which mitigates flooding.

Citizen Science Initiatives: Citizen-led monitoring of water quality often includes observing water levels and flow patterns. Early detection of changes can prompt preventive actions, such as clearing obstructions or reinforcing riverbanks, which help prevent flooding.

Riparian Buffer Planting: Planting vegetation along riverbanks stabilises the soil and reduces erosion. These riparian buffers act as natural sponges, absorbing excess rainwater and slowing down runoff into rivers. This reduces the peak flow during storms, lowering the risk of flooding downstream.

Restoration of Natural Flow: Restoring a river's natural flow allows rivers to manage excess water more effectively. It re-establishes natural floodplains, which can temporarily hold floodwaters and gradually release them, reducing flood peaks.

Creation of River Parks: Urban river restoration projects, like the Cheonggyecheon River, include the creation of green spaces and flood control structures. These parks act as floodways, allowing rivers to overflow safely during heavy rains, which helps protect surrounding urban areas from flooding. This requires putting pressure on our governments to carve out public green infrastructure.

The Brisbane River will always flood, but with better understanding, care, and respect, we may be able to better learn to live alongside what is such an important part of life in Kurilpa. And who knows, with the right management, we might be able to resurrect something of the river’s former abundance and beauty.

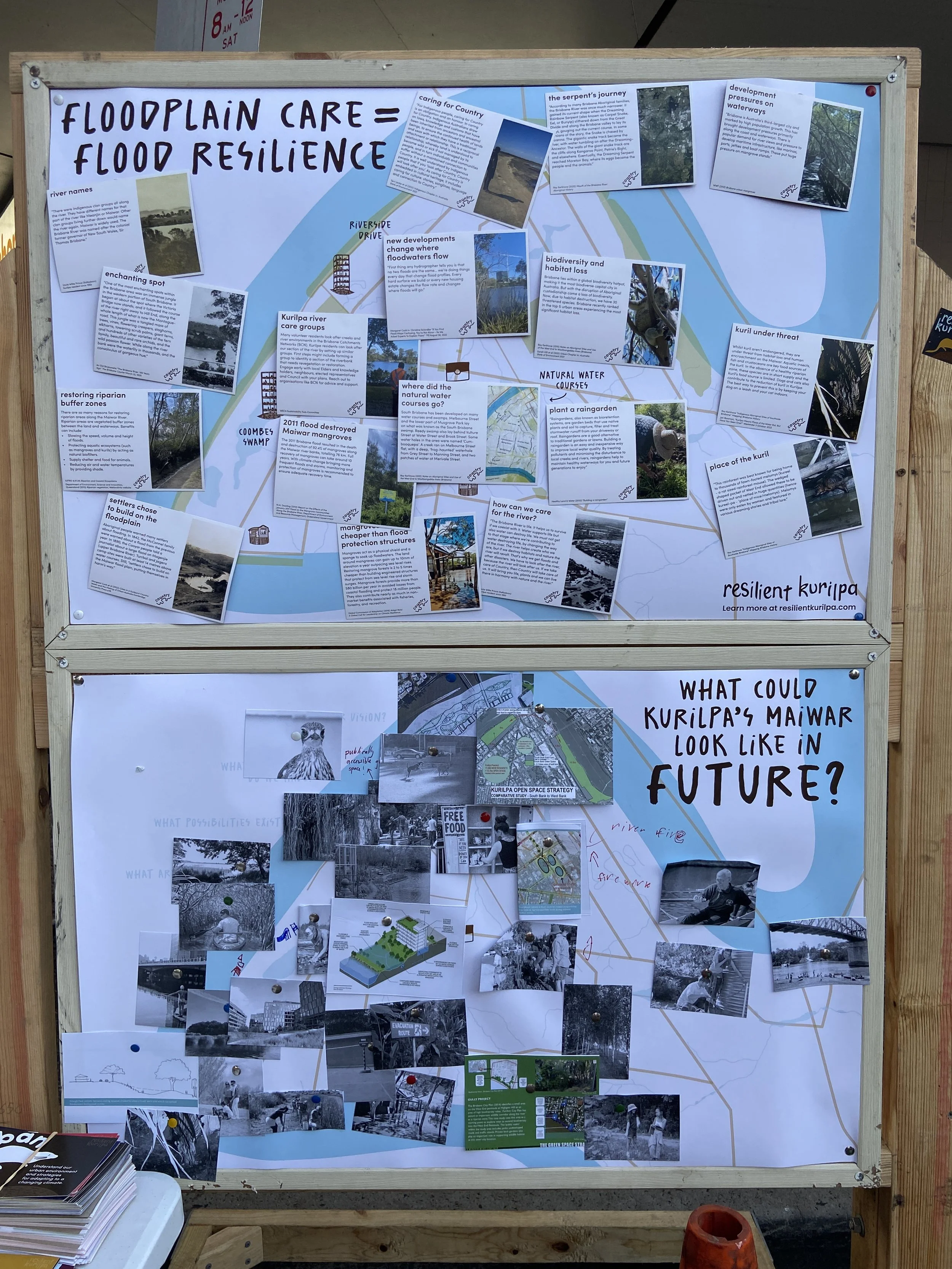

Image: A community-collaged vision of caring for Kurilpa's section of the Maiwar created at the Kurilpa Derby 2024.

Rose Lane is a freelance writer who has lived in Brisbane since 1985 and in 4101 since 2019. She has been a regular contributor to The Westender and was a Community Correspondent with ABC Radio Brisbane from 2014-2016. Her writing has appeared in The Guardian, The Big Issue, New Matilda and other publications.